I’ve spent the summer with a new lift preparing to teach the core Behavioral Economics and Managerial Decisions course at Cornell (AEM 6140). Each year it gets more challenging to think about how we view AI, education, and the future of both work and life. Crafting a policy on AI has also been challenging. Admittedly, this may be the last year I can keep the policy that I’ve had for the past two years.

My general policy has been around embracing AI, but avoiding using AI for core ideas. I believe that some key learning processes and skills development are lost by delegating to AI in the wrong way.

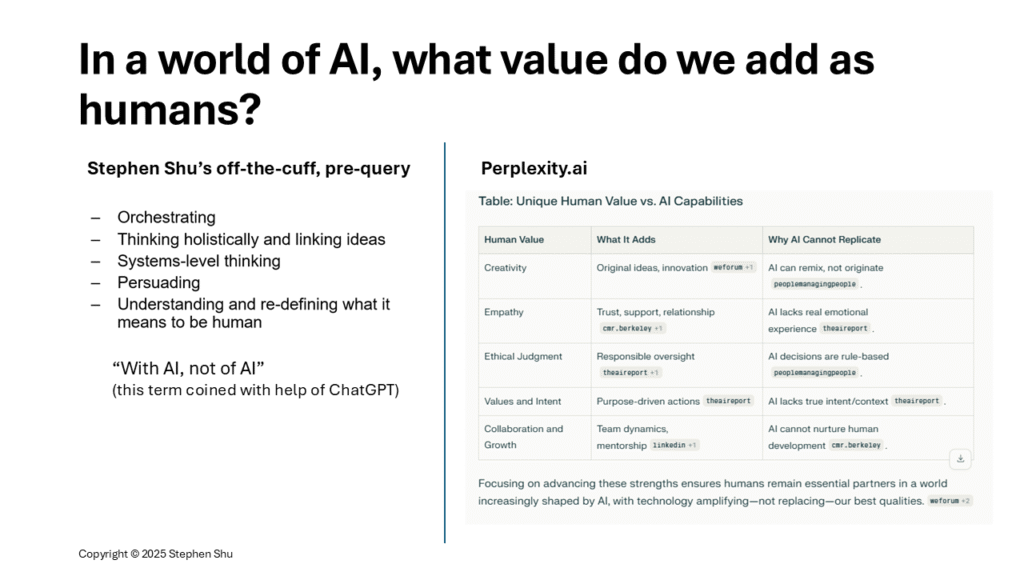

The larger question I pose though is not around AI policy. Rather, I see the key question as what value do we expect to add as humans? This is the type of education, environment, and support structure that I aspire to build toward.

With that as backdrop, I wrote down five things that I will share with students today in the classroom. We add value by:

- Orchestrating

- Thinking holistically and linking ideas

- Using system-level thinking

- Persuading

- Understanding and re-defining what it means to be human

“With AI, not of AI” (term coined with help of ChatGPT to solidify my thinking)

After I drafted my thoughts, I did query Perplexity.ai to try and gather thoughts expressed by others. I see some similarities and differences.

Upon further reflection, I viewed my concept of human value-add as being more organic and aspirational (i.e., something that we’ll need to practice and improve over time as opposed to achieving a milestone).